Motor Espionage: What Does Your Car Know?

Introduction

In an article written in September of 2023, software company Mozilla came out to denounce several automobile companies including, but not limited to, Volkswagen, BMW, Ford, Subaru, Nissan, Tesla, Kia, and Toyota, for major breaches of user privacy. Amongst other crucial pieces of data, they were accused of tracking bits of personal data such as, the age, immigration status, sexual activity, weight, and health of their users. These were obtained through microphones, speakers, and cameras within the vehicles, through taking data from phones connected to the vehicles, through car apps, and through tracking activity on company websites (Mozilla). Knowing this information, one might be curious to know about the specific risks that these policies pose to their personal data.

Background

Before discussing their effects, it is critical to understand that these policies are often vague in their approach to informed consent. Mozilla states the following:

“The very worst offender is Nissan. The Japanese car manufacturer admits, in their privacy policy, to collecting a wide range of information, including sexual activity, health diagnosis data, and genetic data — but doesn’t specify how. They say they can share and sell consumers’ “preferences, characteristics, psychological trends, predispositions, behavior, attitudes, intelligence, abilities, and aptitudes” to data brokers, law enforcement, and other third parties.” (Mozilla)

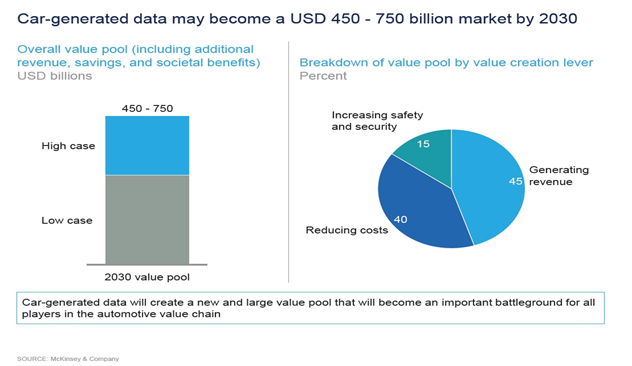

This becomes exacerbated by the fact that these cars can collect data from connected mobile devices without the knowledge of the driver. As with virtually all decisions in the corporate world, there is a financial incentive behind the storing of users’ vehicle data. Car data monetization is expected to become a flourishing industry within the next half decade, with Mozilla claiming, “Analysts estimate that by 2030, car data monetization could be an industry worth $750 billion.” The following table from McKinsey and Company further breaks down the sources of revenue of this $750 billion dollar industry:

While this collection of data may seem borderline illegal, The Detroit News reports that cars have largely gone unprotected by the 4th Amendment. Data harvesting from them thus enters into an uncharted legal gray area. This data can be used for anything from increasing insurance premiums based on speed, number of texts/calls made while driving, and other factors, to being employed in a court setting. (Mozilla)

Finally, according to the same Mozilla article, this data can be turned over to governments and law enforcement agencies upon request. This is not unprecedented. American news outlet, Vice News, reports a 2014 Georgia court case in which data collected from the vehicle driven by the defendant was used as evidence in court. This set a precedent for future cases by which one’s automotive data could be used against them in a legal setting.

It is, however, important to note that this precedent has since been challenged because of its unclear relationship to 4th Amendment right protections. In October of 2019, the Georgia Supreme Court ruled under pressure from the ACLU that all law enforcement must obtain a warrant before seeking to download data from the vehicles of suspects. (Vice News)

Analysis

On June 18th of 2024, the so-called BlackSuit hacker attacked and paralyzed the servers of nearly 15,000 CDK Global (major provider of software to the automotive industry) car dealerships. This attack also saw significant breaches of personal data collected by car companies, including, but not limited to, credit card information, Social Security numbers, names, addresses, and bank account details. According to the American news outlet CBS, CBK Global is now facing a class action lawsuit for negligence of data. As of July 5th, it is speculated that the BlackSuit hacker was part of the BlackSuit Gang, a group composed of Russian and Eastern European hackers. (Transport Topics News)

With all of this information laid out, it becomes clear that car companies are harvesting individuals’ data without their explicit and informed consent, and they have thus far been irresponsible with its contents. As the BlackSuit Hack shows, your data not only has the potential to be used in court, but also by malicious individuals or even foreign governments. Data breaches such as these are also reported to be routine by Mozilla. Barring the alternative of major legal intervention, automotive companies will likely continue to harvest data as a result of the profit motive.

Data monetization can offer some benefits to the customer, such as giving them warnings about road conditions and enhancing speech-controlled functions such as Siri, but there is a concerning lack of control over one’s data. While consumers may be able to simply not use applications in their vehicle or connect Bluetooth services, the reality is that this might impede the vehicle from working properly and limit the use of crucial navigation technology. With so little control from the individual, this battle for privacy becomes the domain of legal scholars and regulatory agencies. It is a harrowing reminder of the limited control of consumers in the absence of legal protection against adverse corporate interests.

Despite this, institutions such as the Georgia Supreme Court and the Federal Trade Commission, recently having made major decisions concerning the use of data, may indicate that a major legal reform concerning data use and the 4th Amendment could be around the corner.

Conclusion

Despite its benefits, car data monetization presents a concerning new paradigm of bypassing informed consent measures. It takes one’s personal information and effectively makes it public without their official and explicit approval. The consumer, as a result of these borderline predatory measures, finds themselves near powerless to stop this incursion on their personal lives. Even if consumers can do little to stop the exploitation of their data, they should continue to inform themselves on what is being monetized, by whom, to whom it is being sold, why it is being sold, and who benefits from this phenomenon.