Myanmar Civil War: An Outlook

Ethnic Divisions and the Myanmar Civil War

Introduction

For over three years, Myanmar has been locked in civil war. With rebel forces gaining ground against the junta’s regime, the civil war looks to be entering its final phase. However, underlying the war are long standing ethnic, racial, and religious tensions that, if not resolved, may lead to the outbreak of another conflict within the near future. This analysis seeks to provide a historical background as well as both short-term and long-term policy recommendations for addressing the coming post-war ethnic tensions in Myanmar.

Historical Background

The civil war began in 2020 after the National League for Democracy won the national elections, defeating the Union Solidarity and Development Party (the military’s political representative). Following their electoral defeat, the military carried out a coup d’etat, imprisoning the leadership of the National League for Democracy and forming a junta to govern in place of the democratically elected government. In September of 2021, militias representing the interests of the deposed National League for Democracy declared war on the junta government, officially beginning the ongoing conflict.

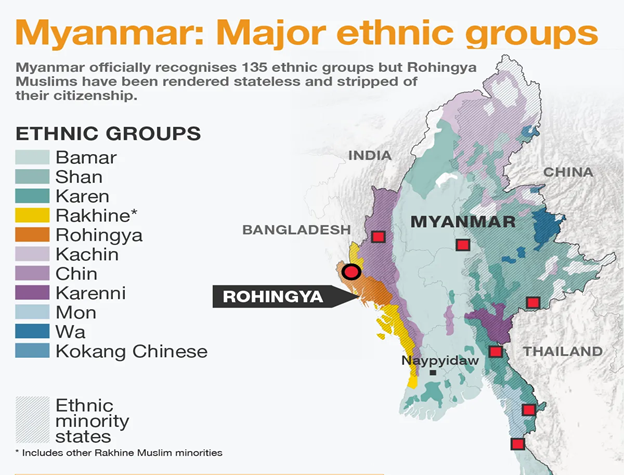

Myanmar’s civil war has causes dating back to the nation’s foundation in 1948. The Burma Independence Act of 1947 created a heterogenous nation in which the dominant Bamar ethnic group only constituted roughly ⅔ to 70% of the total population. Shan, Karen, Arkan, Kokang, Rohingya, and Kayin minorities made up small but considerable portions of the population. These groups have historically suffered economic and political discrimination at the hands of the central government. During the 1960s and the 1980s, minority militia groups pushed for the creation of a federative republic under which they would have regional autonomy. These protests were met with military crackdowns. More recently, the Rohingya minority has been subject to discrimination due to the 969 Movement. This Buddhist nationalist movement espouses anti-Muslim rhetoric and has led to both militia and legislative violence against the Rohingya individuals. Much of the discrimination was supported by the former National League for Democracy government (2016-2021). This government oversaw what the United States Department of State has qualified as a genocide of the Rohingya population of the Rakhine region.

The conflict has largely hardened along ethnic lines, with various ethnic militia groups supporting either side. The junta’s forces are primarily comprised of conscripted Burmese members of the armed forces from Myanmar’s large cities. Many of these cities are concentrated along the Irrawaddy Delta and the rivers which flow into it. They are joined in their fight against rebels by Rohingya militia groups. Importantly, the junta is largely unpopular even among Bamar city dwellers. The Three Brotherhood Alliance, composed primarily of Shan, Arakan, and Kokang fighters, acts as the main force of opposition to the junta. It is the backbone of the National Unity Government and People’s Defence Force, the government-in-exile and armed forces composed of the remnants of the National League for Democracy. Their main ally, the Northern Alliance, is composed of various different minority ethnic groups. The People’s Defence Force and allied forces are primarily concentrated in majority ethnic minority areas on the outskirts of the nation but have since taken roughly 60% of Myanmar’s territory and seem poised to win the civil war. It is important to note that these ethno-political alignments are not absolutes, but rather representative of a larger trend of ethnic groups aligning with either the junta’s forces or the rebel forces.

Figure 2: Ethnic map of Myanmar (Al Jazeera)

A Timeline of the Myanmar Civil War

- February 1st, 2021: After the political party representing military interests (the Union Solidarity and Development Party, or USDP) lost the 2020 election, General Min Aung Hlaing overthrew the democratically elected National League for Democracy (NLD) government and imprisoned its leaders.

- February-March 2021: Hlaing’s coup and formation of a military junta trigger civil unrest. Protestors called for the overthrow of the junta and the restoration of the NLD government.

- May 2021: Armed resistance to the junta’s government begins in earnest. At this point, it is primarily contained to the Shan, Kachin, Kayin, and Bago provinces. However, the Yangon region sees several remote explosive devices detonated. Government crackdowns occur all across the nation. Armed clashes become more and more common near the end of the month, spreading to additional regions.

- September 2021: The National Unity Government (NUG), which was formed by the remaining NLD leaders in opposition to the junta, brings together elements of the armed forces and protestors to form the People’s Defense Force (PDF). The two opposing governments then enter into a state of war.

- Winter, 2021-2022: Fighting escalates from skirmishes into all-out warfare, with the military routinely targeting civilian infrastructure. Of particular concern are indiscriminate air strikes. In November, the PDF amplified both direct confrontations and the number of hit-and-run attacks it conducted using remote explosive devices. During this period, crackdowns become less common, and sabotage of civilian and military infrastructure becomes more common.

- March 2022: Amnesty International accuses the junta of collective punishment following the striking and looting of villages in the Shan and Kayah regions.

- May 2022: The NUG defense minister asks for international support through arms shipments.

- Early 2023: Waves of guerilla attacks target Junta forces.

- Summer, 2023: NUG forces launch a surprise offensive, gaining ground all across the nation.

- Late 2023: Resistance takes control of roughly 60% of Myanmar’s territory after leading several offensives during the Monsoon Season.

- October 2023-January 2024: The Three Brotherhood Alliance undertakes Operation 1027, capturing a large amount of territory throughout the northeast and northern regions of the country.

- November-December 2023: Resistance captures the regional capital of Laukkai, leading to a temporary ceasefire between the Three Brotherhood Alliance and Junta forces which would later expire.

Policy Recommendations

The Myanmar Civil War has exposed the nation’s deeply seeded ethnic tensions as the conflict has been largely fought along ethno-racial lines. Regardless of the outcome of the war, the path towards lasting stability would appear to run through the mending of ethnic tensions. The implementation of regional autonomy for ethnic minorities in particular would seem to be a desirable middle-of-the-road reform. Rather than granting the regions independence, it would ensure that minority groups have some say in local governance while still ultimately answering to the national government. At the same time, it would likely benefit the national government through calming unrest in rebel regions. This would decrease the amount of money and resources that the government would need to invest in putting down rebellions or maintaining security forces all while generally increasing stability on the national level. Military governments in Myanmar have historically resisted the implementation of such a system, meaning that a NUG victory in the civil war would make reform considerably more likely. However, seeing the long history of ethnic rebellions, the military government may still institute moderate reforms in the event of a junta victory. Failure to implement reforms which benefit minority groups may include political instability and the potential for continued and localized armed conflict following the end of the civil war.

The Rohingya minority and 969 Movement require special attention. According to Moshe Yegar, a historian of Islam in South Asia, the group’s repression can be traced to the British colonial period. Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, the “Burma for Burmese” was routinely used at anti-Muslim riots.

More so than other ethnic minorities, this Muslim-majority group was the target of government repression even under democratic leadership. They were stripped of citizenship under the NLD government and remain persecuted under junta rule. Moreover, local tensions within the Rakhine region between Buddhist nationalists and Muslims have been exacerbated by the civil war. According to the Council on Foreign Relations, even before the 2020 coup, local government forces enacted mass killings of Rohingya Muslims as a part of a policy of collective punishment.

Short-term policy solutions should aim to halt legal discrimination of Rohingya individuals and prevent the emergence of violent conflict. Some potential short-term policies include restoring citizenship and setting up local defense forces to ensure the safety of both Rohingya and Buddhist inhabitants of the Rakhine region. These local defense forces should be subject to international law and transparency agreements enforced by the international community to ensure that they do not continue successive governments’ policy of collective punishment. Long term, the government should both ensure total legal equality for the Rohingya population and invest in developing the Rakhine region equitably to ensure a prosperous livelihood. This will decrease incentives to join extremist groups. Failure to implement equitable reforms will likely provoke additional political instability and the development of additional Rohingya terrorist organizations.